The charitable organisation, which is run in such a way as to minimise administration costs and maximise benefits to recipients, has been set up by a close group of friends as a means of honouring the life and ambitions of mountaineer, climber and adventurer, Michael ‘Mick’ Parker.

Parker’s father, Bruce, set up the foundation alongside long-time associate Rob Prior. They then decided they needed to partner with an existing organisation that could act as a conduit for donations into Nepal. It was at this point a partnership with WEF was decided upon.

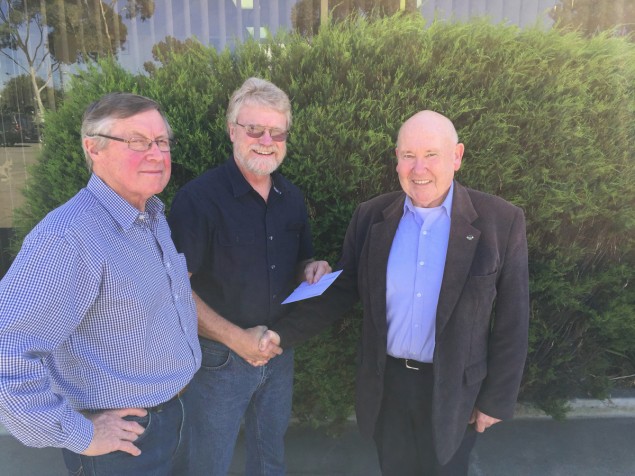

Recently, Wild met the pair along with Ian Williams, director of WEF, to discuss Michael’s story, his aspirations and the initial project on which the foundation seeks to embark.

The Quiet Achiever

Bruce highlighted his son’s “non-conformist” attitude, which singled him out as a unique individual from a very young age.

“Mick didn’t like to do things according to rules or traditions, which meant he was constantly testing boundaries,” Bruce said. “Sometimes they were his own and sometimes they were those of the people around him.”

This independent mindset, combined with an extraordinary aerobic capacity (Michael excelled at long distance and cross-country running from a young age, regularly outpacing his peers, we’re informed) eventually informed his interest in climbing and, eventually, mountaineering. It was in this particular field that his singular lung capacity would serve him best, and Michael is remembered today as a climber that, despite his slight frame, managed to summit five of the Himalayas’ 8,000-metre peaks and attempt eight others, including Everest from the north – without oxygen.

Furthermore, his friends and family remember Michael for his generosity. While he’d established himself as a graphic designer in Melbourne, he worked only enough to fund his next expedition, and he “ended up spending more time in the field than he did at work”, his father said.

“But what little he had with him he was always giving away to the locals,” he continued. “Michael was regularly found going through his packs, rummaging for the money he had stashed away ‘just in case’ and giving it to villagers in need.”

One tale of generosity has been publicised by The Sydney Morning Herald, in which Michael left his tent in order to rescue a lost Irish climber in the middle of a whiteout on K2. Michael was subsequently forced to feel for his own boot prints in the snow in order to lead the man back to his tent.

Rob, who had known Michael from a young age, said that for all his achievements, it was rare to hear the man discuss his trips, whether they were successful or otherwise.

“He’d just returned from his attempt of K2 and I’d asked him how it went,” Rob told Wild. “He just replied as he always did: ‘Oh, it was alright’ or something similar. It was only sometime later that I discovered the only reason he’d turned around was to save this Irish climber from freezing to death.”

“And that wasn’t the only time he’d risked his life for another person in those mountains,” Bruce said.

For all his exploits, Michael hadn’t yet gained any notoriety among the mountaineering or wider community by the time of his death in 2009. At the age of 36, Michael suffered from a pulmonary oedema in the process of climbing Makalu – the world’s fifth highest peak. The first manifestations of the condition caused him to pass out several times as he made his way down the mountain. While he made it safely back to Kathmandu and avoided succumbing to the effects of pulmonary oedema, Michael unfortunately passed away from an unrelated case of asphyxiation the following evening.

Six years on, Michael’s life begins to gather interest. As the subject of a forthcoming biography, Spirit High by James Knight (published by Xoum, available in stores June 2015), and as the inspiration behind the Michael Parker Foundation, the adventurer and graphic designer who managed to avoid the limelight in life is now being gradually drawn into it posthumously.

A Climber’s Legacy

“About three years prior to his death, Michael came to his mother, Gail, and I explaining the situation in Nepal with regards to education,” Bruce said. “Michael spoke of the lack of facilities, the distances that the kids had to travel to get to school and more. He even described having seen lessons given by teachers scrawling with a stick in the dust – that was the kind of education they had access to, and Michael clearly felt for these children.”

Michael had begun discussing ideas to export donated school supplies into Nepal by plane, building a network of hikers and locals that would assist in delivering packages to remote, hillside schools and villages.

“It’s this vision that we want to fulfil,” said Rob. “That’s why we’ve set up the Michael Parker Foundation, and with the assistance of Ian Williams and WEF, we now have a landmark project that we can begin building towards.”

The first step towards realising Michael’s ambitions is to construct and outfit a hostel in the remote village of Suspa Kshamawati in the Dolakha District, Janakpur Zone of north eastern Nepal.

“One of the major challenges for school-age children in these areas is actually getting to school in the first place,” Ian said. “Some of them must travel for long distances to get to school and that’s only when their parents don’t require them to help with harvest duties and the like.”

By building an adequate hostel-and-school facility, children would be able to board throughout the week in safety, rather than traveling long distances in remote, often dangerous, hill country.

“We’re building this hostel level-by-level, providing dormitories for young women as a priority, as we feel education for girls is an absolute necessity in these areas,” he added, “and stage one is already complete.”

Funded by major donations from the Michael Parker Foundation, the Michael Francis Parker hostel in Suspa Kshamawati appears to be well on its way to becoming a reality, with the much-needed education of many Nepalese children soon to follow.

This article orginally appeared in issue 147 of Wild – Australia’s longest running outdoor adventure magazine.